Why Clean Meat Won't Shut Down Factory Farms

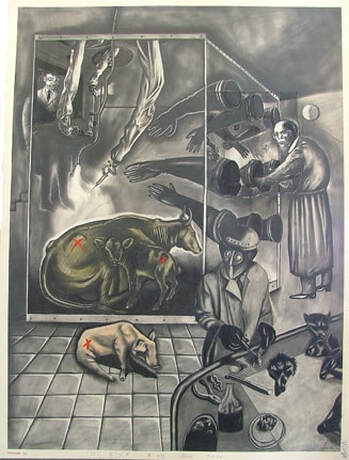

Sue Coe: It Got Away. 1990.

Copyright ©1990 Sue Coe

Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York

Sue Coe: It Got Away. 1990.

Copyright ©1990 Sue Coe

Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York

Advocates for CM ("Clean Meat," or cellular or laboratory-cultivated flesh), predict that, as the costs of raising live animals for meat skyrocket, and as Big Meat companies like Tyson, Perdue, Smithfield, Cargill, etc., invest in synthesized animal meats, the latter will become cheaper and take up an ever growing share of the newly-dubbed "protein" market. Over time, the theory goes, CM will actually replace meat from animals raised on factory farms, thus sparing countless billions of animals terrible suffering.

But Clean Meat won't eliminate animal exploiation (see this page on our website to learn why). It won't even shut down factory farms. Because it isn't meant to.

The most comprehensive and careful studies of cellular meat technology suggest that it may not even be feasible to produce synthetic meat in sufficient quantities, or cheaply enough, to compete with conventional meat. As Joe Fassler has pointed out, the Good Food Institute, in its rosiest prediction, claims that by 2030, a massive high-tech production facility could be built to "produce 10,000 metric tons—22 million pounds—of cultured meat per year." Though that "sounds like a lot," Fassler observes, "that volume would represent more than 10 percent of the entire domestic market for plant-based meat alternatives (currently about 200 million pounds per year in the U.S." Furthermore, that "22 million pounds of cultured protein, held up against the output of the conventional meat industry, barely registers. It’s only about .0002, or one-fiftieth of one percent, of the 100 billion pounds of meat produced in the U.S. each year."

The same dynamics hold in the fisheries industry, where an estimated one to three trillion marine animals are killed each year. Contrary to the optimistic claims of tech enterpreneurs promoting synthesized fish products, there is no evidence that cellular meat can make any dent in the global fish market as a whole. As a reporter for the Guardian notes, the trouble is that cellular fish products would need "to be eaten in numbers high enough to replace wild-caught fish. But "[r]esearchers say this is unlikely, given the fact that aquaculture, the farming of aquatic organisms, hasn’t succeeded in replacing global wild-caught fisheries but is simply adding to seafood production."

Even if we suspend our disbelief and critical thinking skills and imagine that, somehow, some day, synthesized meat products will do far better than we now imagine, the way the technology is being developed and marketed virtually ensures the perpetuation of the conventional meat industry, including meat from animals raised in intensive confinement (factory farms).

According to an article entitled, "How Alternative Proteins Can Support Animal Agriculture," in Tri-State Livestock News, Renée A. Vassilos, an Agricultural Economist with Banyan Innovation Group, was to relay the following good news to other leaders in the meat industry when they met at the April 2019 National Institute for Animal Agriculture conference:

"[Vassilos'] presentation, titled How Alternative Proteins Can Support the Animal Agriculture Industry [will focus] on how the newest, most touted technology innovation, alternative proteins — from insects to legumes to cell cultures — are not something to view as a replacement for animal proteins, but just another competitor in a huge global protein market.'"

We hear the same thing being said over and over by others in the industry, too: cellular meats are not intended to replace meats from living animals raised for slaughter. “We’re taking a yes and ‘Yes and’ as opposed to an either-or approach to the space,'" explains Matthew Walker, managing director at S2G Ventures, a high-tech venture capitalist firm investing in alternative proteins. “'You will have animal-based meat, plant-based meat and you will have hybrid products.'"[1] Analysts with Supermarket News confirmed the strategy in 2020: "Plant-based meat alternatives...are mostly an occasional choice driven by perceived health benefits, being a good source of protein, just something different and for environmental reasons. Blended vegetable/meat items, such as mushroom burgers, have a higher and greater cross-population appeal, and can be a bridge to the societal and health benefits people look for, while keeping meat on the plate."

It's a "win-win" for everybody--except for the billions of animals who will continue to be raised and killed for their flesh. Mostly, though, it is a "win" for the powerful corporations and wealthy investors who see cellular meat, blended products, and plant-based products as an opportunity to make a lot of money. As Charles Mitchell observes in The Baffler: "Mimicking the meat giants, aspiring to their mammoth production and monopolistic tyranny, is to build a 'new' industry in the image of the world’s ugliest business. More likely than not, in the coming years, company valuations will continue to explode. More celebrities will be made, and profits will be plentiful. But if I were a chicken, I wouldn’t be cheering."

The cellular meat strategy relies on Big Meat to make the scheme work. By the admission of its leading proponents, Clean Meat will only begin replacing meat from factory-farmed animals if CM products are of high quality and are able to be produced en masse as cheaply as meat products derived from animals reared in factory farms. Once this happens, if it ever does, it would then be left to the big meat companies to move the products. The meat companies, the thinking goes, are already in the business of marketing meat, and if anyone can make Clean Meat acceptable to the public, it's them. Only they already have the marketing prowess, manufacturing capability, name recognition, distribution chains, and gargantuan advertising budgets needed to reengineer the public's consumption habits. The meat economy is like an ocean liner steaming towards an ice field, and only the powerful engines of the animal industry, the thinking goes, can slow its momentum and put it into reverse.

With this strategy in mind, the Good Food Institute, New Crop Capital, Clear Current Capital, and other key players in the Clean Meat lobby have sought, and won, investment money from factory farming behemoths. Tyson, for example, has invested in the Clean Meat start-ups, Memphis Meats and Future Meats. PHW-Gruppe Lohmann & Co., one of the largest poultry producers in Europe (the company kills 350 million chickens every year) has invested in Supermeats. And so on. The fly in this ointment, however, is Big Meat itself, which cannot be entrusted with the future fate of hundreds of billions of animals. Unfortunately, while key players in Big Meat have indeed begun investing in both vegan and CM products, there is right now no evidence--zero--that these corporate killers of animals are planning to phase out their animal agriculture operations any time soon--or indeed ever. On the contrary, their avowed strategy is to invest in CM as a way of dominating future "protein" markets by offering consumers a wider, more diverse array of meat products. So eliminating "conventional" meat from animals raised in intensive confinement is not even on the table. Violence against animals will continue, only it will be hidden in the skirts of "consumer choice." As Karen Davis observes, "A dilemma that will likely arise in future with 'clean meat' versus slaughterhouse meat: certain foods could be labeled 97% 'clean' meat and 3% 'animal protein'--along the lines of Paul Shapiro’s Better Meat Co. today, which helps meat companies produce products labeled, say, 70% plant protein and 30% animal protein." Former animal welfare executive Nick Cooney, who was drummed out of the movement over credible sexual harassment allegations, has founded two venture capitalist firms, New Crop and Lever VC, which are also helping animal agribusiness blur the distinction between plants and animals. Perdue now sells just "blended" products produced partly with capital provided by Lever, including "Chicken Plus": "Perdue's latest innovation PERDUE® Chicken Plus™ blends cauliflower, chickpeas and plant protein to create the next generation of frozen chicken nuggets, tenders and patties, and each serving is complete with one-quarter cup (half a serving of vegetables) and is made with 100 percent all-natural ingredients...."

For agribusiness and animal killers like Cargill and Tyson, investing in Clean Meat start-ups, as well as in vegan food companies, makes good business sense for three reasons:

1. It allows them to "greenwash" their violent enterprises, under cover of "sustainability," "compassion," and other Orwellian euphemisms.

2. It hedges against future risk, by giving the meat industry growing strategic influence and advantage over the vegan market (and even, indirectly, over the animal rights movement itself) at a time when animal agriculture is more and more associated with global ecological breakdown.

3. It helps to ensure future dominance of the market in animal products, by creating a diverse portfolio of emerging "protein" products.

That Big Meat companies in fact have no intention of ending, or even scaling back, their production of meat from living animals can be seen in their recent investment decisions and annual reports to shareholders. Cargill is a good example. The company has said quite clearly that it is interested in Clean Meat as a component of a strategy to expand its reach in the "proteins" market--not as a way of ending its "traditional" farmed animal business. Brian Sikes, Cargill's Protein group leader, explains:

"Our goal is to provide a complete basket of goods to our customers. We will do this by growing our traditional protein business, entering into new proteins and investing in innovative alternatives....At Cargill, we recognize that meat is a core part of consumer diets and central to many cultures and traditions. We believe consumers will continue to choose meat as a protein source, and that is why we are focused on bringing it to their table as sustainably and cost-effectively as we can. Our traditional proteins, as well as new innovations like cultured meats, are both necessary to meet that demand.”

To underscore this strategy, Cargill has meanwhile continued to invest heavily in its factory farming infrastructure:

"Cargill is committed to growing our protein portfolio. This includes investing in, and growing, our traditional protein businesses....Our commitment is reinforced by nearly $600 million in recent investments in conventional protein in North America alone, including the acquisition of Five Star Custom Foods, modernization of our turkey hatchery in Virginia and the conversion of our Columbus, Neb., plant into a cooked meats facility. Also, CAN’s recent acquisition of Southern States Cooperatives’ animal feed business and our investment in the NouriTech FeedKind facility in Memphis further underscores Cargill’s overarching commitment to animal protein...."[2]

Does that sound like Cargill is planning to wind down its mass extermination of animals any time soon? If so, why would Cargill sink an additional half a billion dollars into its factory farming operations? There is simply no evidence that the meat companies are planning to get out of the business of exploiting and killing animals. Rather, as the human population continues to grow, and as demand for meat increases (in no small measure due to the aggressive marketing campaigns of the meat companies themselves), it will be necessary for the industry to respond with a variety of products--including beef, chicken, pork, eggs, fish, and dairy from actual animals, not only or even primarily meat from cell cultures. Already, Paul Shapiro, author of the book Clean Meat, is helping companies get a bigger bang for their buck by mixing plant proteins in with their burgers. His so-called "blended burger" project is creating plant-meat hybrids that will further blur the boundaries between vegan and meat products, confusing customers and creating new opportunities for the meat industry to greenwash their commodities.

A Two-Track Strategy: Catch and Kill (then Dominate the Market)

As part of the strategy to dominate both the vegan/CM market as well as "traditional" meat markets for years to come, Big Meat--with an assist from Big Pharma--has been busy quietly buying up almost all of the extant vegan enterprises on the market:

The push for Clean Meat is merely an extension of Big Meat's strategy dominate the so-called protein market. As Robert Grillo, of Free from Harm, writes: "My biggest concern with clean meat is that the meat conglomerates buy up the technology and the rights from smaller start ups in an effort to control if and how these products are ever marketed and sold. The worst case scenario would be a 'catch and kill' strategy in which they buy it up only to shelve it, thereby preventing those who would otherwise use it to advance some social, public good." (See a longer analysis of Clean Meat by Robert Grillo here.)

Here, the Clean Meat advocate might well ask, Nu? So? Who cares if Big Meat owns the vegan and CM foods industry? Won't that help expand the market in alternative foods, thus reducing the number of animals being killed? In fact, we don't know the answer to that question. What we do know, however, is that Clean Meat in itself won't end animal agriculture in any of its present forms, including intensive confinement--not without some transformation of the public's understanding of what and who animals are, and why their lives matter.

At best, Clean Meat will help produce a market in which, say, 40 billion land animals are killed each year, rather than 50 billion. But even that "optimistic" scenario comes with strings attached, as thick and twisting as the cables holding up the Brooklyn Bridge.

Given growing human population pressures and rising levels of consumption in the developing world, the global meat market is expected to expand in coming years and decades. Some incalculable part of this expansion is naturally going to be driven by the animal industry itself. And since the latter is committed to maintaining a diverse portfolio of "protein products"--meat from farmed animals raised in CAFOs, meat from farmed animals raised organically and on smaller farms, synthesized or lab-grown meat, vegan products, and food made from ground-up insects (yes, that's a thing--and it's being promoted by Bill Gates, one of the backers of Clean Meat)--we have no way of knowing how many animals are going to continue to be killed to satisfy the market in meat.

Nor do we know whether the capitalists in control of these new technologies will ultimately find it more profitable to market inexpensive Clean Meats (which could compete with meat from factory farms) or only high-end, "boutique" meat products. In fact, the scalability problem is so great that cellular meat companies appear to be quietly down-scaling their ambitions. As Michele Simon, director of the Plant-Based Foods Association, observed in December 2022: "We keep hearing about 'scaling' but no company has commercialized anything yet." Simon concludes that "biotech meat seems pretty far off from viable commercialization. That means companies will be making small batches if anything, which will remain very expensive. This could explain why Upside Foods is cozying up to high-end chefs and talking about restaurant tastings. While this may be a valid way to taste-test some products, it’s also a sure sign that anything close to price parity with animal meat is a long way away."

Even analysts at the Good Food Institute have publicly admitted that the technology might chiefly or only be used to produce high-end meat products, like foies gras or lamb chops. "[Liz] Specht [of the Good Food Institute] says the clean meat industry might make more of a foothold for itself by growing high-end cuts of meat such as steak or lamb chops. Since these cuts have more complex structures, with intricate arrangements of fat, muscle and connective tissue, they require some kind of scaffolding to make certain kinds of cells grow in different positions. Specht even thinks that clean meat could eventually bring the cost down of what are traditionally more expensive cuts of meat, while plant-based alternatives flood the lower end of the market."[4]

Jevons Paradox

Further uncertainty is introduced into this equation by Jevons Paradox. According to this theory from environmental economics, policies that spur technological efficiency in resource use can lead to increased consumption of that very resource, thus cancelling out the gains. For example, people who buy Priuses may drive more than they did before, since it's now cheaper to do so (because they spend less money on gas), and also because they psychologically associate driving their car with "being green." The energy and environmental savings of driving a hybrid may thus be cancelled out. Some analyses suggest that it may even better to drive your old gas-guzzling Chevy into the ground than to junk it for a brand new Prius, because of the huge amounts of energy and natural resources required to produce such a complex car.

It is likely that we will see a similar dynamic develop in meat markets, if the Clean Meat lobby is allowed to have its way. Imagine a future market in which meat from animals and meat from bioengineering vats both have a role to play. Rather than trying to convince the public to move steadily towards plant-based foods, the meat industry is likely to reinforce consumers' dependency on flesh. This is something, after all, the meat industry that has worked very hard at for a century to do (and with historically stunning success: postwar per capita meat consumption in the US grew by 400%). Now, due to the bad press around the catastrophic ecological effects of animal agriculture, meat is in crisis, and will be for some time. How, then, can the animal industry have its traditional meat, and have others eat it, too? The answer is by continuing to keep people accustomed to high levels of meat consumption. In developing markets like China, the meat industry is already working hard to increase per capita meat consumption.

Due to the ecological limits of live animal production, alternative meats--both plant-based and cellular--are needed to meet rising demand. But this doesn't necessarily mean that we'll soon be seeing a radical decline in the number of animals being killed. Suppose, say, that 30% of the human population replaces much of their farmed animal meat with CM or synthesized meat. Would that translate into a 30% decline in the number of animals being killed globally to satisfy the burgeoning meat market? We don't know. Because population is still growing, and per capita demand for meat--thanks to Big Meat itself, which invests hundreds of millions of dollars in advertising for meat--is growing, too. It is entirely possible that the overall number of land animals being killed will remain the same, if not grow, in the coming decades. (The prospect for seafood markets is less clear, since the fisheries industry is exterminating marine life at such a blistering pace that soon there won't be any more marine animals left to exploit.)

Ironically, because the Clean Meat lobby is intent "to take ethics off the table for the consumer," as Bruce Friedrich puts it, we may see a scenario in which consumers simply broaden their palates, eating Clean Meats sometimes, CAFO meats some times, so-called "humane" meats other times, and vegan burgers at still other times. In short, the numbers of animals being killed may indeed go down. But then it is likely to stabilize, leading to a perpetuum mobile of suffering, violence, and mass slaughter--forever.

Proponents of Clean Meat like to present themselves as "pragmatists" and realists, in contrast to supposed the "idealists" and ineffectual moralists of the animal rights movement. In their telling, even engaging in unethical forms of research, such as using Bovine Fetal Serum in developing clean meat, or engaging in animal testing, are acceptable, because "the end justifies the mean." But just what is "the end"? Clearly, it is not a future in which millions and even billions of animals are not brutally killed each and every year. Nor is it a future in which the human race is asked to confront its depraved contempt for nonhuman animal life, whether in the slaughterhouse or in the wild. Instead, it is a future much like the present.

Utilitarians will argue that if Clean Meat is able to reduce the overall number of animals being killed, it will have been worth it. Are they right? Only if we discount the problem of justice. Would a world in which, say, "only" three million Jews and Roma had died at the hands of the Nazis, rather than six million, really have been "better"? Only in an abstract sense. Genocide is by definition a form of singularity, a phenomenon of horror and injustice that is fundamentally irreducible. To say that three million Jews dying would have been acceptable, or even "a success," is to play an intellectual game that demeans the victims of Nazi violence. Had only a single child been murdered by the Nazis, it would have been unacceptable.

By the same token, to flippantly argue, as Clean Meat proponents do, that we have to sacrifice our vision of animal justice in favor of a "success" in which billions will continue to die, is morally repugnant, at best. At worst, it is to betray the interests of the countless animals who will continue to die, year after year. Even the staunchest utilitarian must take into consideration the lost opportunities of the "road not taken." What do we lose, what do we risk, in walking away from the abolitionist vision? What might happen if consumers in the future do not have Clean Meat as an option, but are made to choose between universal veganism and the certain destruction of the earth by animal agriculture? If we don't resist Clean Meat now, we may never know.

Though CM proponents pass lightly over the subject, the technological, marketing, and cultural hurdles that stand in the way of mass-marketed Clean Meat remain enormous. Will synthetic flesh become so inexpensive to produce that it will be able to compete with meat from animals raised factory-farms? Will Clean Meat taste as good as real meat? We have no way of knowing the answers to these questions. However, even if CM can be manufactured cheaply and in high quality some day--as of July 2021, the management consulting giant McKinsey and Co. was predicting that cultivated meat won't achieve price parity with conventional animal meat until 2030, if then-- the retail price and marketing of CM products will be determined by the cold calculations of the manufacturers who make them. So if Tyson, say, decides that it can make more money by marketing "boutique" synthetic meats to the environmentally conscious, wealthy, Whole Foods shopper, than by marketing generic products for consumers used to buying CAFO-produced flesh, then it will do the former. Tens of billions of animals will still be exploited and killed, even if the Clean Meat market grows.

The reason Clean Meats are unlikely ever to replace meat from live animals, including ones confined in factory farms, is because there are very powerful institutional, economic, and cultural forces in play to ensure that never happens. And to the extent that the animal advocacy movement is helping to promote the myth that we need meat, that meat is "natural," and so on, it is strengthening those very forces.

[1] "How Alternative Proteins Can Support the Animal Agriculture Industry," Tri-State Livestock News, March 19, 2019. https://www.tsln.com/news/how-alternative-proteins-can-support-the-animal-agriculture-industry/. Jonathan Shieber, "Lab-grown Meat Could Be on Store Shelves by 2022, Thanks to Future Meat Technologies," TechCrunch.com, Oct. 10, 2019. https://techcrunch.com/2019/10/10/lab-grown-meat-could-be-on-store-shelves-by-2022-thanks-to-future-meat-technologies/.

[2] Cargill, August 23, 2017. https://www.cargill.com/story/protein-innovation-cargill-invests-in-cultured-meats.

[3] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-12-19/the-vegetarians-at-the-gate.

[4] Matt Reynolds, "The Clean Meat Industry Is Racing To Ditch Its Reliance on Foetal Blood," Wired, March 20, 2018. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/scaling-clean-meat-serum-just-finless-foods-mosa-meat.

But Clean Meat won't eliminate animal exploiation (see this page on our website to learn why). It won't even shut down factory farms. Because it isn't meant to.

The most comprehensive and careful studies of cellular meat technology suggest that it may not even be feasible to produce synthetic meat in sufficient quantities, or cheaply enough, to compete with conventional meat. As Joe Fassler has pointed out, the Good Food Institute, in its rosiest prediction, claims that by 2030, a massive high-tech production facility could be built to "produce 10,000 metric tons—22 million pounds—of cultured meat per year." Though that "sounds like a lot," Fassler observes, "that volume would represent more than 10 percent of the entire domestic market for plant-based meat alternatives (currently about 200 million pounds per year in the U.S." Furthermore, that "22 million pounds of cultured protein, held up against the output of the conventional meat industry, barely registers. It’s only about .0002, or one-fiftieth of one percent, of the 100 billion pounds of meat produced in the U.S. each year."

The same dynamics hold in the fisheries industry, where an estimated one to three trillion marine animals are killed each year. Contrary to the optimistic claims of tech enterpreneurs promoting synthesized fish products, there is no evidence that cellular meat can make any dent in the global fish market as a whole. As a reporter for the Guardian notes, the trouble is that cellular fish products would need "to be eaten in numbers high enough to replace wild-caught fish. But "[r]esearchers say this is unlikely, given the fact that aquaculture, the farming of aquatic organisms, hasn’t succeeded in replacing global wild-caught fisheries but is simply adding to seafood production."

Even if we suspend our disbelief and critical thinking skills and imagine that, somehow, some day, synthesized meat products will do far better than we now imagine, the way the technology is being developed and marketed virtually ensures the perpetuation of the conventional meat industry, including meat from animals raised in intensive confinement (factory farms).

According to an article entitled, "How Alternative Proteins Can Support Animal Agriculture," in Tri-State Livestock News, Renée A. Vassilos, an Agricultural Economist with Banyan Innovation Group, was to relay the following good news to other leaders in the meat industry when they met at the April 2019 National Institute for Animal Agriculture conference:

"[Vassilos'] presentation, titled How Alternative Proteins Can Support the Animal Agriculture Industry [will focus] on how the newest, most touted technology innovation, alternative proteins — from insects to legumes to cell cultures — are not something to view as a replacement for animal proteins, but just another competitor in a huge global protein market.'"

We hear the same thing being said over and over by others in the industry, too: cellular meats are not intended to replace meats from living animals raised for slaughter. “We’re taking a yes and ‘Yes and’ as opposed to an either-or approach to the space,'" explains Matthew Walker, managing director at S2G Ventures, a high-tech venture capitalist firm investing in alternative proteins. “'You will have animal-based meat, plant-based meat and you will have hybrid products.'"[1] Analysts with Supermarket News confirmed the strategy in 2020: "Plant-based meat alternatives...are mostly an occasional choice driven by perceived health benefits, being a good source of protein, just something different and for environmental reasons. Blended vegetable/meat items, such as mushroom burgers, have a higher and greater cross-population appeal, and can be a bridge to the societal and health benefits people look for, while keeping meat on the plate."

It's a "win-win" for everybody--except for the billions of animals who will continue to be raised and killed for their flesh. Mostly, though, it is a "win" for the powerful corporations and wealthy investors who see cellular meat, blended products, and plant-based products as an opportunity to make a lot of money. As Charles Mitchell observes in The Baffler: "Mimicking the meat giants, aspiring to their mammoth production and monopolistic tyranny, is to build a 'new' industry in the image of the world’s ugliest business. More likely than not, in the coming years, company valuations will continue to explode. More celebrities will be made, and profits will be plentiful. But if I were a chicken, I wouldn’t be cheering."

The cellular meat strategy relies on Big Meat to make the scheme work. By the admission of its leading proponents, Clean Meat will only begin replacing meat from factory-farmed animals if CM products are of high quality and are able to be produced en masse as cheaply as meat products derived from animals reared in factory farms. Once this happens, if it ever does, it would then be left to the big meat companies to move the products. The meat companies, the thinking goes, are already in the business of marketing meat, and if anyone can make Clean Meat acceptable to the public, it's them. Only they already have the marketing prowess, manufacturing capability, name recognition, distribution chains, and gargantuan advertising budgets needed to reengineer the public's consumption habits. The meat economy is like an ocean liner steaming towards an ice field, and only the powerful engines of the animal industry, the thinking goes, can slow its momentum and put it into reverse.

With this strategy in mind, the Good Food Institute, New Crop Capital, Clear Current Capital, and other key players in the Clean Meat lobby have sought, and won, investment money from factory farming behemoths. Tyson, for example, has invested in the Clean Meat start-ups, Memphis Meats and Future Meats. PHW-Gruppe Lohmann & Co., one of the largest poultry producers in Europe (the company kills 350 million chickens every year) has invested in Supermeats. And so on. The fly in this ointment, however, is Big Meat itself, which cannot be entrusted with the future fate of hundreds of billions of animals. Unfortunately, while key players in Big Meat have indeed begun investing in both vegan and CM products, there is right now no evidence--zero--that these corporate killers of animals are planning to phase out their animal agriculture operations any time soon--or indeed ever. On the contrary, their avowed strategy is to invest in CM as a way of dominating future "protein" markets by offering consumers a wider, more diverse array of meat products. So eliminating "conventional" meat from animals raised in intensive confinement is not even on the table. Violence against animals will continue, only it will be hidden in the skirts of "consumer choice." As Karen Davis observes, "A dilemma that will likely arise in future with 'clean meat' versus slaughterhouse meat: certain foods could be labeled 97% 'clean' meat and 3% 'animal protein'--along the lines of Paul Shapiro’s Better Meat Co. today, which helps meat companies produce products labeled, say, 70% plant protein and 30% animal protein." Former animal welfare executive Nick Cooney, who was drummed out of the movement over credible sexual harassment allegations, has founded two venture capitalist firms, New Crop and Lever VC, which are also helping animal agribusiness blur the distinction between plants and animals. Perdue now sells just "blended" products produced partly with capital provided by Lever, including "Chicken Plus": "Perdue's latest innovation PERDUE® Chicken Plus™ blends cauliflower, chickpeas and plant protein to create the next generation of frozen chicken nuggets, tenders and patties, and each serving is complete with one-quarter cup (half a serving of vegetables) and is made with 100 percent all-natural ingredients...."

For agribusiness and animal killers like Cargill and Tyson, investing in Clean Meat start-ups, as well as in vegan food companies, makes good business sense for three reasons:

1. It allows them to "greenwash" their violent enterprises, under cover of "sustainability," "compassion," and other Orwellian euphemisms.

2. It hedges against future risk, by giving the meat industry growing strategic influence and advantage over the vegan market (and even, indirectly, over the animal rights movement itself) at a time when animal agriculture is more and more associated with global ecological breakdown.

3. It helps to ensure future dominance of the market in animal products, by creating a diverse portfolio of emerging "protein" products.

That Big Meat companies in fact have no intention of ending, or even scaling back, their production of meat from living animals can be seen in their recent investment decisions and annual reports to shareholders. Cargill is a good example. The company has said quite clearly that it is interested in Clean Meat as a component of a strategy to expand its reach in the "proteins" market--not as a way of ending its "traditional" farmed animal business. Brian Sikes, Cargill's Protein group leader, explains:

"Our goal is to provide a complete basket of goods to our customers. We will do this by growing our traditional protein business, entering into new proteins and investing in innovative alternatives....At Cargill, we recognize that meat is a core part of consumer diets and central to many cultures and traditions. We believe consumers will continue to choose meat as a protein source, and that is why we are focused on bringing it to their table as sustainably and cost-effectively as we can. Our traditional proteins, as well as new innovations like cultured meats, are both necessary to meet that demand.”

To underscore this strategy, Cargill has meanwhile continued to invest heavily in its factory farming infrastructure:

"Cargill is committed to growing our protein portfolio. This includes investing in, and growing, our traditional protein businesses....Our commitment is reinforced by nearly $600 million in recent investments in conventional protein in North America alone, including the acquisition of Five Star Custom Foods, modernization of our turkey hatchery in Virginia and the conversion of our Columbus, Neb., plant into a cooked meats facility. Also, CAN’s recent acquisition of Southern States Cooperatives’ animal feed business and our investment in the NouriTech FeedKind facility in Memphis further underscores Cargill’s overarching commitment to animal protein...."[2]

Does that sound like Cargill is planning to wind down its mass extermination of animals any time soon? If so, why would Cargill sink an additional half a billion dollars into its factory farming operations? There is simply no evidence that the meat companies are planning to get out of the business of exploiting and killing animals. Rather, as the human population continues to grow, and as demand for meat increases (in no small measure due to the aggressive marketing campaigns of the meat companies themselves), it will be necessary for the industry to respond with a variety of products--including beef, chicken, pork, eggs, fish, and dairy from actual animals, not only or even primarily meat from cell cultures. Already, Paul Shapiro, author of the book Clean Meat, is helping companies get a bigger bang for their buck by mixing plant proteins in with their burgers. His so-called "blended burger" project is creating plant-meat hybrids that will further blur the boundaries between vegan and meat products, confusing customers and creating new opportunities for the meat industry to greenwash their commodities.

A Two-Track Strategy: Catch and Kill (then Dominate the Market)

As part of the strategy to dominate both the vegan/CM market as well as "traditional" meat markets for years to come, Big Meat--with an assist from Big Pharma--has been busy quietly buying up almost all of the extant vegan enterprises on the market:

- In 2016, the Danone dairy company in France purchased the White Wave Company, producers of Silk brand soymilk products.

- In 2017, Field Roast and Lightlife, the vegan meat companies, were purchased by Maple Leaf Foods, the biggest killer of animals in Canada (biggest meat packer). In 2020, Lightlife/Maple Foods weaponized the Good Food Institute's "clean meat" discourse to attack the two most successful companies marketing vegan meats in the US--Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods--in a full-page advertisement in the New York Times that used the word "clean" three times to differentiate its ostensibly less "processed" products from its competitors. (https://www.forbes.com/sites/jennysplitter/2020/08/25/lightlife-letter-impossible-beyond/#485efdac2b65)

- In 2017, the Daiya Vegan Cheese company was purchased by the Otsuka pharmaceutical company--the second biggest pharma in Japan, and a tester on animals.

- In 2017, Nestlé USA (which has been implicated in animal violence, not to mention in the infant formula scandal) purchased Sweet Earth Foods, a vegan manufacturer.

- In 2018, the Good Catch vegan seafood company "raised $8.7 million in new funding from backers, including the aforementioned PHW-Gruppe Lohmann & Co.[3]

The push for Clean Meat is merely an extension of Big Meat's strategy dominate the so-called protein market. As Robert Grillo, of Free from Harm, writes: "My biggest concern with clean meat is that the meat conglomerates buy up the technology and the rights from smaller start ups in an effort to control if and how these products are ever marketed and sold. The worst case scenario would be a 'catch and kill' strategy in which they buy it up only to shelve it, thereby preventing those who would otherwise use it to advance some social, public good." (See a longer analysis of Clean Meat by Robert Grillo here.)

Here, the Clean Meat advocate might well ask, Nu? So? Who cares if Big Meat owns the vegan and CM foods industry? Won't that help expand the market in alternative foods, thus reducing the number of animals being killed? In fact, we don't know the answer to that question. What we do know, however, is that Clean Meat in itself won't end animal agriculture in any of its present forms, including intensive confinement--not without some transformation of the public's understanding of what and who animals are, and why their lives matter.

At best, Clean Meat will help produce a market in which, say, 40 billion land animals are killed each year, rather than 50 billion. But even that "optimistic" scenario comes with strings attached, as thick and twisting as the cables holding up the Brooklyn Bridge.

Given growing human population pressures and rising levels of consumption in the developing world, the global meat market is expected to expand in coming years and decades. Some incalculable part of this expansion is naturally going to be driven by the animal industry itself. And since the latter is committed to maintaining a diverse portfolio of "protein products"--meat from farmed animals raised in CAFOs, meat from farmed animals raised organically and on smaller farms, synthesized or lab-grown meat, vegan products, and food made from ground-up insects (yes, that's a thing--and it's being promoted by Bill Gates, one of the backers of Clean Meat)--we have no way of knowing how many animals are going to continue to be killed to satisfy the market in meat.

Nor do we know whether the capitalists in control of these new technologies will ultimately find it more profitable to market inexpensive Clean Meats (which could compete with meat from factory farms) or only high-end, "boutique" meat products. In fact, the scalability problem is so great that cellular meat companies appear to be quietly down-scaling their ambitions. As Michele Simon, director of the Plant-Based Foods Association, observed in December 2022: "We keep hearing about 'scaling' but no company has commercialized anything yet." Simon concludes that "biotech meat seems pretty far off from viable commercialization. That means companies will be making small batches if anything, which will remain very expensive. This could explain why Upside Foods is cozying up to high-end chefs and talking about restaurant tastings. While this may be a valid way to taste-test some products, it’s also a sure sign that anything close to price parity with animal meat is a long way away."

Even analysts at the Good Food Institute have publicly admitted that the technology might chiefly or only be used to produce high-end meat products, like foies gras or lamb chops. "[Liz] Specht [of the Good Food Institute] says the clean meat industry might make more of a foothold for itself by growing high-end cuts of meat such as steak or lamb chops. Since these cuts have more complex structures, with intricate arrangements of fat, muscle and connective tissue, they require some kind of scaffolding to make certain kinds of cells grow in different positions. Specht even thinks that clean meat could eventually bring the cost down of what are traditionally more expensive cuts of meat, while plant-based alternatives flood the lower end of the market."[4]

Jevons Paradox

Further uncertainty is introduced into this equation by Jevons Paradox. According to this theory from environmental economics, policies that spur technological efficiency in resource use can lead to increased consumption of that very resource, thus cancelling out the gains. For example, people who buy Priuses may drive more than they did before, since it's now cheaper to do so (because they spend less money on gas), and also because they psychologically associate driving their car with "being green." The energy and environmental savings of driving a hybrid may thus be cancelled out. Some analyses suggest that it may even better to drive your old gas-guzzling Chevy into the ground than to junk it for a brand new Prius, because of the huge amounts of energy and natural resources required to produce such a complex car.

It is likely that we will see a similar dynamic develop in meat markets, if the Clean Meat lobby is allowed to have its way. Imagine a future market in which meat from animals and meat from bioengineering vats both have a role to play. Rather than trying to convince the public to move steadily towards plant-based foods, the meat industry is likely to reinforce consumers' dependency on flesh. This is something, after all, the meat industry that has worked very hard at for a century to do (and with historically stunning success: postwar per capita meat consumption in the US grew by 400%). Now, due to the bad press around the catastrophic ecological effects of animal agriculture, meat is in crisis, and will be for some time. How, then, can the animal industry have its traditional meat, and have others eat it, too? The answer is by continuing to keep people accustomed to high levels of meat consumption. In developing markets like China, the meat industry is already working hard to increase per capita meat consumption.

Due to the ecological limits of live animal production, alternative meats--both plant-based and cellular--are needed to meet rising demand. But this doesn't necessarily mean that we'll soon be seeing a radical decline in the number of animals being killed. Suppose, say, that 30% of the human population replaces much of their farmed animal meat with CM or synthesized meat. Would that translate into a 30% decline in the number of animals being killed globally to satisfy the burgeoning meat market? We don't know. Because population is still growing, and per capita demand for meat--thanks to Big Meat itself, which invests hundreds of millions of dollars in advertising for meat--is growing, too. It is entirely possible that the overall number of land animals being killed will remain the same, if not grow, in the coming decades. (The prospect for seafood markets is less clear, since the fisheries industry is exterminating marine life at such a blistering pace that soon there won't be any more marine animals left to exploit.)

Ironically, because the Clean Meat lobby is intent "to take ethics off the table for the consumer," as Bruce Friedrich puts it, we may see a scenario in which consumers simply broaden their palates, eating Clean Meats sometimes, CAFO meats some times, so-called "humane" meats other times, and vegan burgers at still other times. In short, the numbers of animals being killed may indeed go down. But then it is likely to stabilize, leading to a perpetuum mobile of suffering, violence, and mass slaughter--forever.

Proponents of Clean Meat like to present themselves as "pragmatists" and realists, in contrast to supposed the "idealists" and ineffectual moralists of the animal rights movement. In their telling, even engaging in unethical forms of research, such as using Bovine Fetal Serum in developing clean meat, or engaging in animal testing, are acceptable, because "the end justifies the mean." But just what is "the end"? Clearly, it is not a future in which millions and even billions of animals are not brutally killed each and every year. Nor is it a future in which the human race is asked to confront its depraved contempt for nonhuman animal life, whether in the slaughterhouse or in the wild. Instead, it is a future much like the present.

Utilitarians will argue that if Clean Meat is able to reduce the overall number of animals being killed, it will have been worth it. Are they right? Only if we discount the problem of justice. Would a world in which, say, "only" three million Jews and Roma had died at the hands of the Nazis, rather than six million, really have been "better"? Only in an abstract sense. Genocide is by definition a form of singularity, a phenomenon of horror and injustice that is fundamentally irreducible. To say that three million Jews dying would have been acceptable, or even "a success," is to play an intellectual game that demeans the victims of Nazi violence. Had only a single child been murdered by the Nazis, it would have been unacceptable.

By the same token, to flippantly argue, as Clean Meat proponents do, that we have to sacrifice our vision of animal justice in favor of a "success" in which billions will continue to die, is morally repugnant, at best. At worst, it is to betray the interests of the countless animals who will continue to die, year after year. Even the staunchest utilitarian must take into consideration the lost opportunities of the "road not taken." What do we lose, what do we risk, in walking away from the abolitionist vision? What might happen if consumers in the future do not have Clean Meat as an option, but are made to choose between universal veganism and the certain destruction of the earth by animal agriculture? If we don't resist Clean Meat now, we may never know.

Though CM proponents pass lightly over the subject, the technological, marketing, and cultural hurdles that stand in the way of mass-marketed Clean Meat remain enormous. Will synthetic flesh become so inexpensive to produce that it will be able to compete with meat from animals raised factory-farms? Will Clean Meat taste as good as real meat? We have no way of knowing the answers to these questions. However, even if CM can be manufactured cheaply and in high quality some day--as of July 2021, the management consulting giant McKinsey and Co. was predicting that cultivated meat won't achieve price parity with conventional animal meat until 2030, if then-- the retail price and marketing of CM products will be determined by the cold calculations of the manufacturers who make them. So if Tyson, say, decides that it can make more money by marketing "boutique" synthetic meats to the environmentally conscious, wealthy, Whole Foods shopper, than by marketing generic products for consumers used to buying CAFO-produced flesh, then it will do the former. Tens of billions of animals will still be exploited and killed, even if the Clean Meat market grows.

The reason Clean Meats are unlikely ever to replace meat from live animals, including ones confined in factory farms, is because there are very powerful institutional, economic, and cultural forces in play to ensure that never happens. And to the extent that the animal advocacy movement is helping to promote the myth that we need meat, that meat is "natural," and so on, it is strengthening those very forces.

[1] "How Alternative Proteins Can Support the Animal Agriculture Industry," Tri-State Livestock News, March 19, 2019. https://www.tsln.com/news/how-alternative-proteins-can-support-the-animal-agriculture-industry/. Jonathan Shieber, "Lab-grown Meat Could Be on Store Shelves by 2022, Thanks to Future Meat Technologies," TechCrunch.com, Oct. 10, 2019. https://techcrunch.com/2019/10/10/lab-grown-meat-could-be-on-store-shelves-by-2022-thanks-to-future-meat-technologies/.

[2] Cargill, August 23, 2017. https://www.cargill.com/story/protein-innovation-cargill-invests-in-cultured-meats.

[3] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-12-19/the-vegetarians-at-the-gate.

[4] Matt Reynolds, "The Clean Meat Industry Is Racing To Ditch Its Reliance on Foetal Blood," Wired, March 20, 2018. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/scaling-clean-meat-serum-just-finless-foods-mosa-meat.